Thanksgiving is this week, and in the time-honored tradition of lazy journalists everywhere, you are sure to see scads of articles decrying the myth that tryptophan in turkey causes post-Thanksgiving drowsiness. Just see today's

Huffington Post,

among many others. (If you need a good, science-based debunking of the myth, see Dr. Aaron Carroll's

short video from this week. Play it for your disbelieving relatives tomorrow as well.)

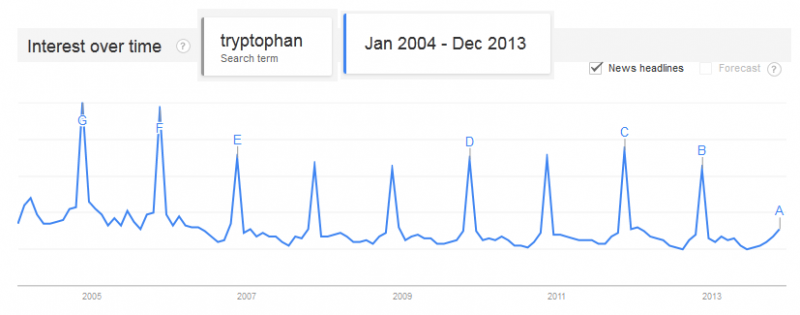

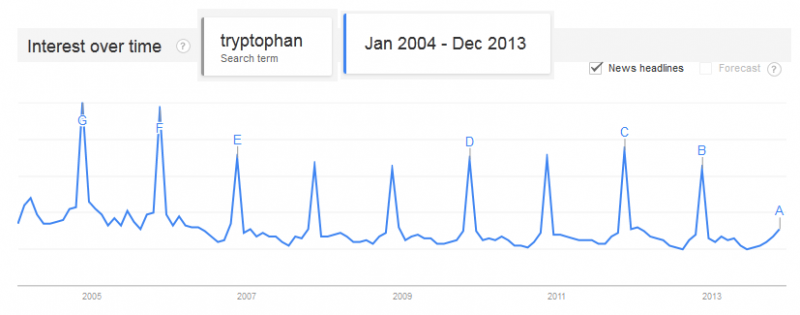

The Annual Tradition: Google trends data for "tryptophan" 2005-2013:

But where did this myth come from? It hasn't existed forever, to be sure. If

Marty McFly cracked a tryptophan joke when he traveled back to 1955, you can be sure that no one would have gotten the joke -- the myth didn't exist yet. In fact, coming from 1985, its questionable whether Marty himself would have made the joke. By 1995 he certainly could have.

Thanks to mattress manufacturers and a Japanese chemical company.

The Origin of the Turkey Tryptophan Myth

Prior to the mid-1970s, the amino acid known as "tryptophan" was rarely mentioned in the press, and never in connection with sleep. For example, a 1952

report suggested that low tryptophan levels might help prevent paralysis from polio. (Yes, this was back when awful common diseases like polio were still around and scared everyone witless.) And in the late 1960s, some folks

said they wanted to genetically increase the supply of the chemical in corn to up its protein content. Yum? Also, by the early 1970s, the Japanese were

gung ho about using tryptophan-rich plankton for food. Double Yum!

Interestingly, whether tryptophan was even in turkey seemed to be in question -- one doctor in 1968

reported that a turkey diet might be a cure for psoriasis because tryptophan "is found in all meats

except turkey". Needless to say, no one was making "tryptophan-haze" jokes as an excuse to not help clean up the Thanksgiving table in 1968.

In 1975, however, a Tufts University study found that tryptophan, at least given in tablet form, appeared to make study participants fall asleep faster and sleep more soundly. This was cited at the time as

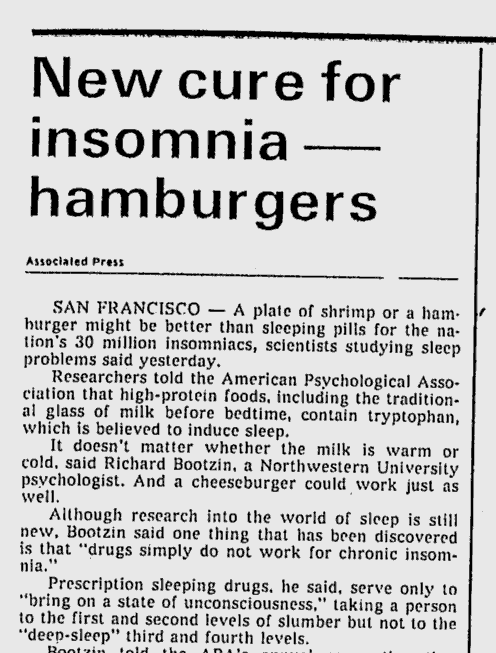

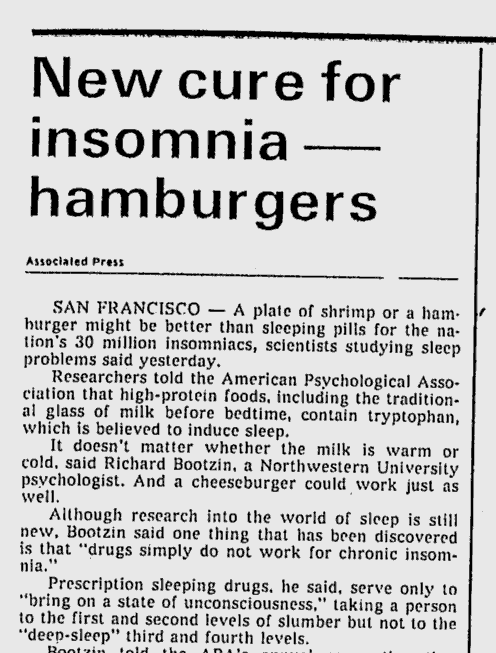

evidence supporting the old claim that drinking a glass of warm milk before bed might have some truth to it. And in 1977, an Associated Press

article reported that not only milk, but other high protein foods with tryptophan could also induce sleep. The

Miami News version of that article was amusingly titled

"New cure for insomnia - hamburgers".

But people didn't start joking that their Big Macs were lulling them to sleep. Into this nascent area of sleep research stepped our good friends, big corporations. At the same time this early research about tryptophan and sleeping was coming to light, the American mattress industry formed a group known as the "Better Sleep Council". Though this ostensible non-profit group claimed to only want to aid humans in their pursuit of sleep, and thus have more satisfying lives, its real purpose was to, of course, SELL MORE MATTRESSES. Getting people to think more about how they sleep, and how to sleep well, is one of the goals of the group, because this might GET YOU TO BUY MORE MATTRESSES. Of course, the "Better Sleep Council" couldn't just demand we "buy mattresses" and nothing else. They had to come up with "studies" and "reports" that looked scientific, and address other things that maybe could effect sleep (INCLUDING NEW MATTRESSES).

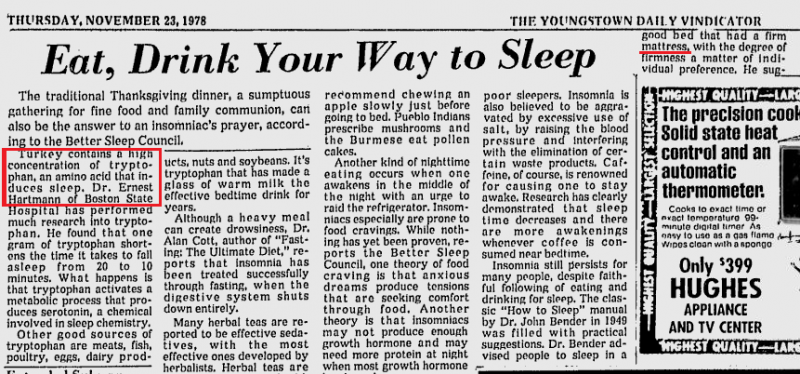

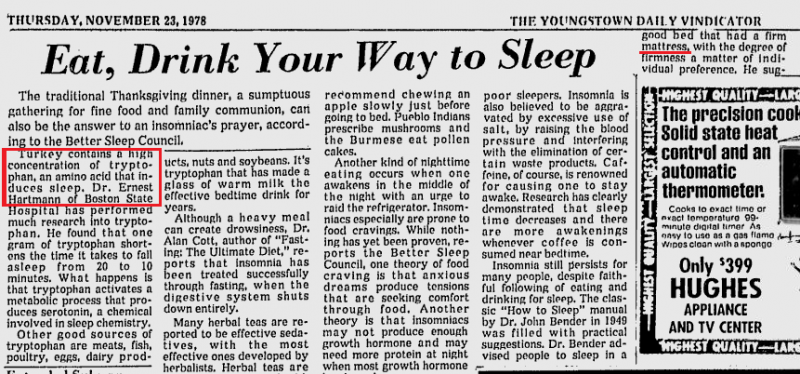

So, for Thanksgiving 1978, the Council released a report to entice holiday-related coverage from lazy journalists. "The traditional Thanksgiving dinner, a sumptuous gathering for fine food and family communion,

can also be the answer to an insomniac's prayer, according to the Better Sleep Counsel." Oh yes. "Turkey contains a high concentration of tryptophan, an amino acid that induces sleep." Now, of course, there had been no studies of whether turkey itself induced sleep; the Council was just highlighting turkey since it was Thanksgiving. And while the Council did note that other foods are also "good sources" of tryptophan, it left the impression that turkey was better.

The Council also recited a number of other things that might possibly help one sleep, before concluding that a "good bed with a firm mattress" might be the real solution. (YOU DON'T SAY!) And benignly enough, the Better Sleep Council

would continue to include turkey and tryptophan among its list of potential cures for insomnia through the 1980s.

But mattress manufacturers are not the only party to blame here.

Health Food Stores: How Many Thing Do They Sell That Can Kill You?

Tryptophan also began to be sold in tablet form in health food stores by the early 1980s as an insomnia cure. And since turkey was one of the foods frequently mentioned as containing tryptophan, and since people do get sleepy after gorging themselves on Thanksgiving, this became "evidence". Though there were some naysayers. For Turkey Day 1986, for example, the "National Turkey Board" (GOAL: EAT MORE TURKEY!)

assured Americans that its the big meal, not the tryptophan, causing sleepiness.

As the claim that tryptophan tablets could cure insomnia continued to spread, the Japanese chemical company Showa Denko greatly stepped up its production of tryptophan in the late 1980s. In fact, the majority of tryptophan tablets sold in the United States all originated from the company, and to keep up with demand, the company

made many changes in its manufacturing process to boost production. Like removing the step of removing impurities. Oops. What's the worst that could happen, right?

Well, you could kill people. Which is what happened. Over 25 deaths and many cases of serious illness from

Eosinophilia-Myalgia Syndrome (EMS) resulted from taking the drug. At the time, the fact that the production was probably contaminated was not known, and calls to ban the drug permanently as the cause of the disease outbreak were

sounding by Thanksgiving 1989. A ban was put in place. Showa Denko ended up

paying $2 billion to settle lawsuits arising out of its conduct.

All this news coverage of tryptophan and its claimed effects actually served to spread the theory that eating turkey on Thanksgiving would make you drowsy. By 1992, newspapers could run an article with a headline like

this:

This November 26, 1992 piece in the

Lakeland Ledger is a high-water mark example of the tryptophan-turkey-sleep connection. It claimed that the tryptophan in turkey will make you sleepy, and also that all those carbs you eat will "accelerate" the process! Even though a Butterball Turkey spokesperson told the reporter than you'd have to eat 21 ounces of turkey (7 servings) to get sleepy, readers were told that adding those carbs make will "it happen faster." Wow! Its science!!

By the mid-1990s, direct refutations of the turkey-tryptophan myth began to appear in the press, but it was already too late. Of course, there would be no need to refute the myth, if the news media hadn't already help create it. But for every article saying "

don't blame the turkey", there would be

other articles lazily restating the basic story as a probable truth. And casual references to turkey-tryptophan-induced sleepiness became common, without reference to whether or not it was true; it was now accepted. As snopes.com

notes, a November 1997 episode of Seinfeld was able to casually mention the tryptophan claim over a turkey dinner. Everyone knew it.

Since at least 2004 (and some

earlier examples), every

serious article to look at the subject is adamant to debunk the myth. But the myth is now so firmly ensconced in our culture that its now an annual ritual of Thanksgiving to write articles debunking the myth. Just as it will be a ritual for your Uncle Walter to declare that the tryptophan's effects are settling in on everyone. Articles promoting the link still pop up from time to time. It's all in how the article is slanted. A November 2006

report on CNN claimed "there may be more at work than just tryptophan" although "Experts say it has a calming effect that can make you sleepy." These sorts of stories perpetuate the myth.

What will we have to tweet about tomorrow otherwise?

The Council also recited a number of other things that might possibly help one sleep, before concluding that a "good bed with a firm mattress" might be the real solution. (YOU DON'T SAY!) And benignly enough, the Better Sleep Council

The Council also recited a number of other things that might possibly help one sleep, before concluding that a "good bed with a firm mattress" might be the real solution. (YOU DON'T SAY!) And benignly enough, the Better Sleep Council